Al Seef

The colloquial Arabic word Al-Seef translates into English as ‘water’s edge’, and denotes geography or stretches of land located along a coast.

Historically, the development of settlements, and subsequently of civilizations, relied heavily on their proximity to a water source. Apart from aiding in sustenance, it increased opportunities for travel and trade, allowing coastal regions to enjoy increased access to wealth and power. Its role as a mediator of voyages also meant that it often facilitated political clashes and wars over larger geographical territories.

Being a valuable element of communal life, water has also become embedded into the cultural fabric of many societies. It is often the central subject of legends, rituals and in some cases even religious denominations.

This exhibition offers a window into several distinct episodes of history, where proximity to water has either shaped or played a significant role in the development of a place. Similar to shining a spotlight on select and specific areas of a stage, this exhibition highlights several individual moments of history, outlined below, which took place and unfolded in coastal regions and in the presence of eminent waters.

1. Establishment of folklore traditions on the Nile

The River Nile, being the backbone of ancient Egyptian civilization, has inspired myths and beliefs associated with nearly every aspect of human life along its banks.

The ancient Egyptian story of creation begins with a sacred and endless body of water called ‘Nun’, out of which a pyramid-shaped mound appeared. On the mound sat a god, who brought light into the world and set the process of creation into motion. This legend is evocative of a scene ancient Egyptians witnessed on an annual basis with the flooding of the Nile, as the river’s waters rose and engulfed small islands and surrounding coastal areas, making them disappear from human sight. When the waters subsided, flooded lands would appear again, similar to mounds arising from sacred ‘Nun’ as recalled by the legend.

The work of Adam Henein entitled ‘Marie Nilus’ depicts a female entity with fin-like features. Those fins, as well as the word ‘Nilus’ in the work’s title, affiliate the sculpture with the River Nile. The word ‘Marie’ references the Virgin Mary, who through centuries has come to be considered a symbol of motherhood in visual imagery across the world. Considering the stories simultaneously, the Virgin Mary and the Nile both appear to have participated in sacred creation and given birth to the divine. Adam Henein marries the symbolic references of both stories within a single work, creating a composite narrative of life’s origin and formation.

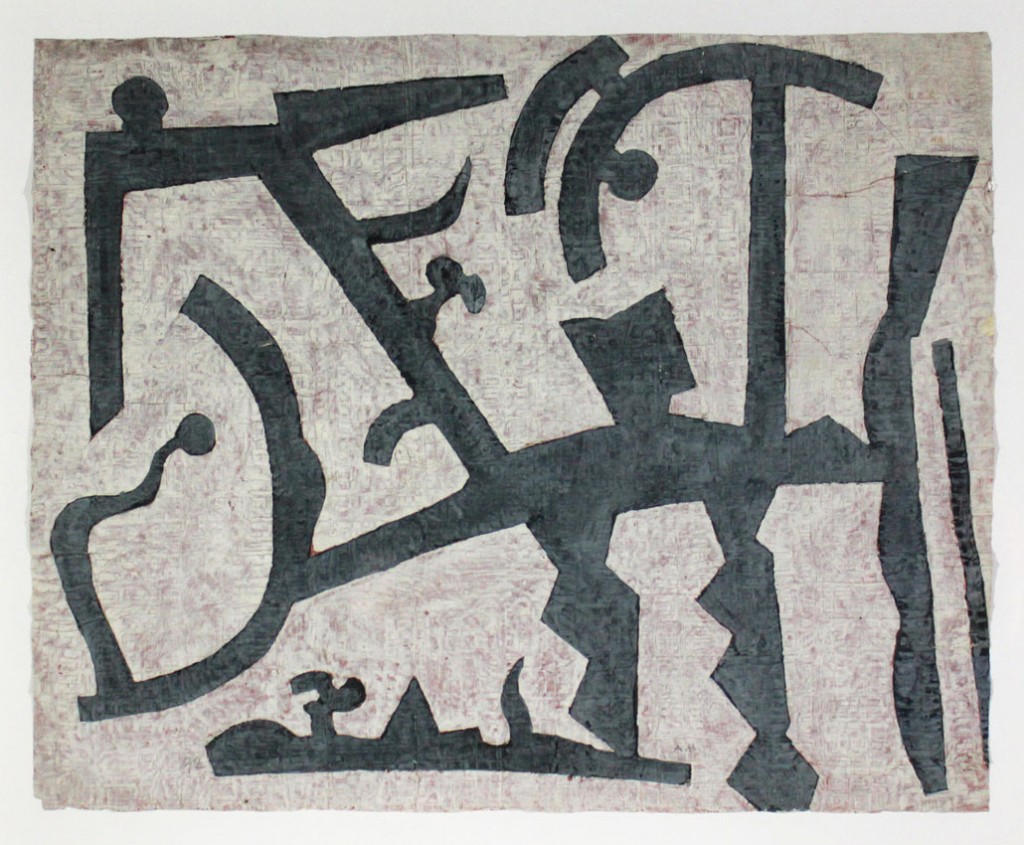

Henein’s work ‘Papyrus’ also evokes the qualities of Egypt’s great river, making use of a plant native to Nile’s banks as a canvas. He creates a composition reminiscent of hieroglyphs on a papyrus sheet, alluding to the custom of writing as practiced by the inhabitants of Nile’s coast, using an aquatic plant and water-based pigments.

2. Building of the Aswan Dam and its implications

The exhibited works of Ragheb Ayad, Effat Nagy and Raafat Ishak all reference the Aswan Dam, situated across the Nile River in Egypt. Construction of the dam closely followed the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, during which King Farouk I was overthrown and a republican regime was established. Two years later, Gamal Abdel Nasser assumed a leading post in the Egyptian government, and spearheaded both the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and the building of the Aswan High Dam. Construction of the dam became a political objective for the Egyptian government in their aspiration towards the country’s industrialisation. The project was also viewed as a glorious ambition of the Arab Nationalist movement, otherwise known as Pan-Arabism, which would showcase Egypt’s achievements in the fields of modern engineering and construction to the rest of the world. This was meant to be a project of monumental scale, one that would provide numerous jobs and unite people with a shared goal and a single purpose. The process of construction, however, unveiled a number of negative implications. Thousands of people had to be resettled, several archaeological sites were threatened with flooding, and many lives were lost during the physical building process due to unsafe conditions and lack of appropriate machinery.

Ragheb Ayad’s ‘Aswan’ executed in 1964, depicts a multitude of anonymous workers, toiling away at the large-scale project, seemingly turning into miniature parts of a gigantic machine. The work, which is believed to be a commissioned piece, confronts the challenges of manual labour and addresses the relationship between individuals and far-reaching visions of those in authority. This painting also serves as evidence of an immense reshaping of the landscape that took place with the development of the High Dam. The altered topography of the coast brought about changes in settlements, lifestyle and impacted wildlife in nearby areas.

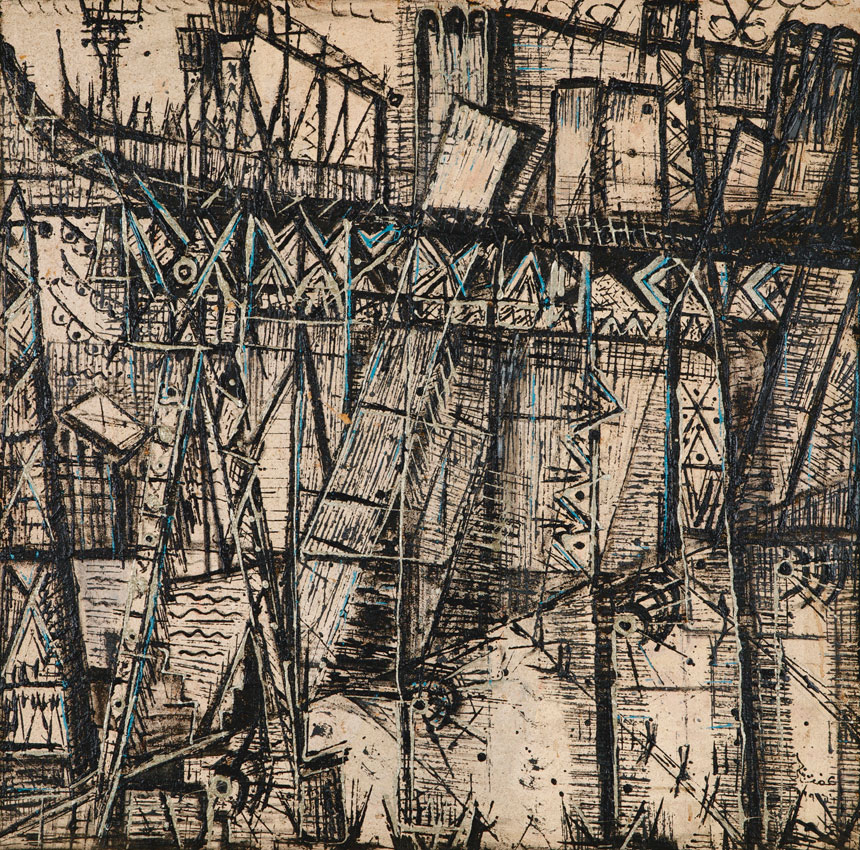

In the early 1960s, the Egyptian Ministry of Culture selected a group of artists to be sent to Upper Egypt to capture scenes of ancient Nubia before they were engulfed by the dam’s water, and also to document the building of the dam itself. Effat Nagy, an Alexandria-born artist, was appointed for this initiative and, along with a group of peers, she made her way south. In the few years that followed, her approach towards painting visibly transformed and she added a new visual vocabulary to her repertoire. Watching the industrial project unfold, Nagy became fascinated with mechanical systems and geometry, and took a step towards darker tones as well as more pronounced abstraction. Her 1966 piece ‘The High Dam’ demonstrates her preoccupation with industrial building elements that densely occupied the landscape during this period, and captures the seemingly robotic dynamics of the construction process. Unlike Ayad, Nagy omits the human and the individual from her depiction of the construction site and allows her work to take on a Futuristic aesthetic.

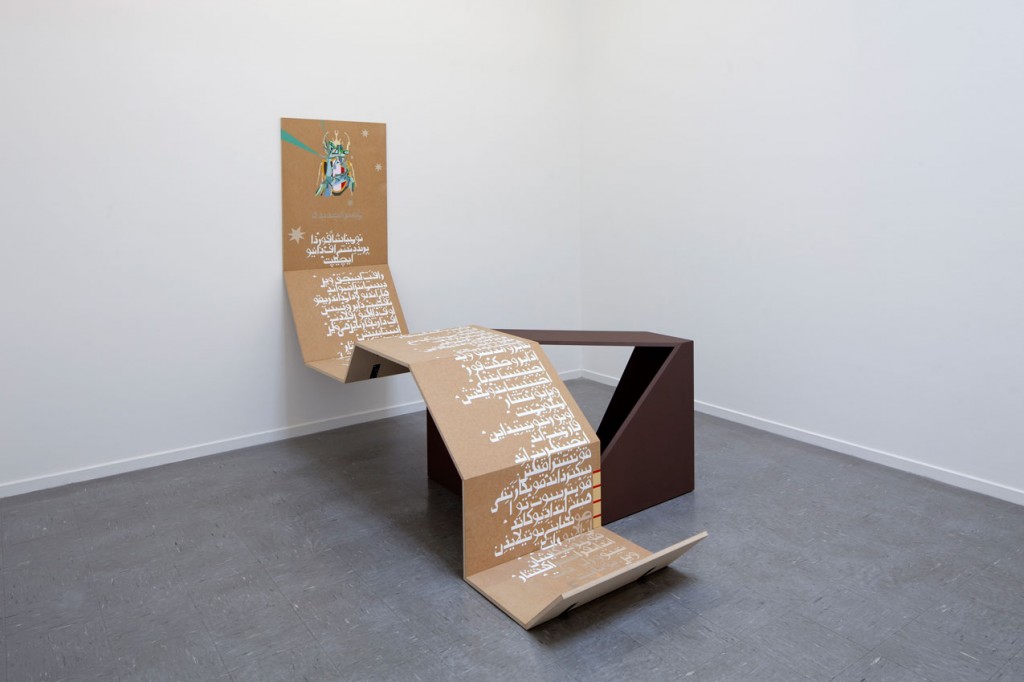

In 2012, more than 40 years after the official opening of Egypt’s High Dam, artist Raafat Ishak transforms it into a timely reference in his work ‘Nomination for the Presidency of the New Egypt’. This sculptural piece, visually resembling a rolled-out papyrus scroll, represents a fictional manifesto written by an imaginary presidential candidate running for office in the post-Mubarak government. The English text of the manifesto transliterated into Arabic script, calls, among other things, for the dismantling of both High and Low Aswan dams and the re-flooding of the Nile. Ishak argues for the practical benefits of re-flooding to Egypt’s farming and agriculture, while the call for deconstruction of the High Dam – a project that was at the core of Egypt’s post-revolution modernisation and socialist regime in the 1960s – represents a metaphoric deconstruction of Egypt’s turbulent history and a political rebirth of the country. The coat of arms that Ishak has selected for the manifesto depicts a species of scarabs that was brought to extinction during the construction of the dam.

3. Political confrontations on the banks of the Tigris

The Tigris is one of the two great rivers flowing through the fertile lands of Mesopotamia – an area corresponding to modern day Iraq and parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran, known as the fertile crescent and widely recognised as the birthplace of some of the world’s earliest civilizations. Being an invaluable agricultural resource, the Tigris has sustained life along its banks for millennia, supporting the development of settlements and eventually the birth of empires in its vicinity. It is believed that along the banks of the Tigris the wheel was invented and channelled irrigation for crops was first employed.

Alongside early technological developments, areas around the Tigris River have also experienced frequent political unrest and the river’s water was often impacted by military actions. One instance of the Tigris tangibly suffering an aftermath of political conflict occurred in 1258, during the siege of Baghdad by Hulagu Khan of Mongolia. This is when the Grand Library of Baghdad was destroyed, while scientists and philosophers were killed and tossed into the river along with countless volumes of books and historical documents, allegedly turning the water black with ink and red with blood.

In the years leading up to and closely following the Iraqi revolution of 1958, when the Hashemite monarchy was overthrown, the Tigris witnessed another surge of violence along its banks. The military activity of this period resulted again in a large number of massacred victims being released into the river’s water, turning the once placid and beautiful element of Iraq’s landscape into a terrifying sight. In more recent history, areas around the Tigris remain in political turmoil and sectarian conflict. The Iraq war having begun in 2003 has brought another wave of brutality and bloodshed to the area; phenomena that continue to permeate the region.

Nazar Yahya, an artist born and raised near the Tigris, witnessed episodes of peaceful life in Baghdad during his childhood and developed warm and pleasant associations with the river. Today, however, his memories no longer correspond to the tainted reality of political circumstances along its banks, and he describes the Tigris as “a river that conceals anonymous massacred victims, feeding the fish in its waters”. Yahya’s works presented in this exhibition all reference the Tigris and the multiple layers of history associated with its waters. The artist employs simplified symbols and isolated references to marine life to allude to the various individual aspects of the river and its past.

4. Movement of Tangier’s inhabitants through the Strait of Gibraltar

Located at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, a stretch of water that links the Mediterranean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, Tangier has always been a place of strategic importance and a meeting point of many cultures. Situated on the North African coast, this Moroccan city overlooks Spanish territories across the Strait’s waters.

Since 1912, Morocco has formally existed under a French protectorate, with some of its regions being controlled by Spain. At this time, Tangier was allotted a special international status and was governed by international law, attracting numerous foreign diplomats, authors and entrepreneurs to its soil. In 1956, through negotiations led by Sultan Mohammed V of Morocco, the country’s independence was restored and subsequently the city of Tangier was reintegrated into Morocco’s rule. Tangier remained a very popular destination for visitors and in the years that followed its coastal areas began experiencing a boom of construction and rapid development of the tourism industry. However, these developments did not always reflect positively on the native inhabitants of the city, causing adverse environmental and ecological impacts, as well as social reverberations and resettlement of the local population.

Following the establishment of the Schengen Agreement by the European Union in 1991, the international movement of Moroccan citizens became restricted. They continued to receive large numbers of foreign tourists, but could no longer travel abroad with ease. This resulted in a magnified desire to cross borders and elevated the Strait’s status to that of a coveted escape route. It became the body of water that could lead one to, or separate one from, Spain or the UK-governed Gibraltar.

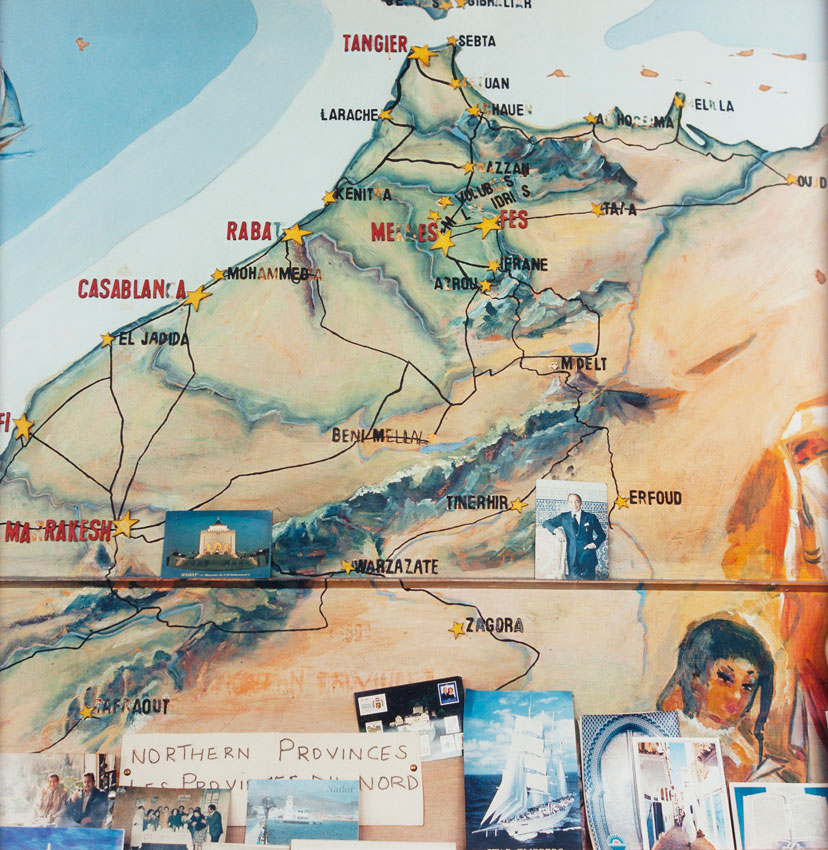

Much of Yto Barrada’s work addresses the question of mobility and implications of the fast growing tourist industry on Tangier. Her photographs capture intimate encounters with commonplace objects and everyday scenes, navigating between poetry and political reality. The work presented in this exhibition shows a map of the northern provinces of Tangier. A map is a representation of large-scale objects on a miniature scale. It reduces the vast and monumental to a proportion that can be easily manipulated. It is also a representation of borders, routes, and size hierarchies. As well as this, Barrada’s map appears to be a very tangible and familiar object – a feeling accentuated by its worn-out surface and an array of photographs and postcards situated at the bottom.

5. Transformation of coastal landscapes in the Gulf

The 1970s and the decades that followed, saw a boom of modernisation, economic growth and urban development in the lands surrounding the Arabian Gulf. Prior to this time, several states within the region, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar and the Trucial Sheikhdoms existed under a British protectorate. The discovery of oil in the region, and the subsequent beginning of its export by Abu Dhabi in 1962, began a shift towards the eventual end of treaty relationships with Britain in 1971. This is when the Trucial States joined forces to form the United Arab Emirates, while Bahrain and Qatar became independent.

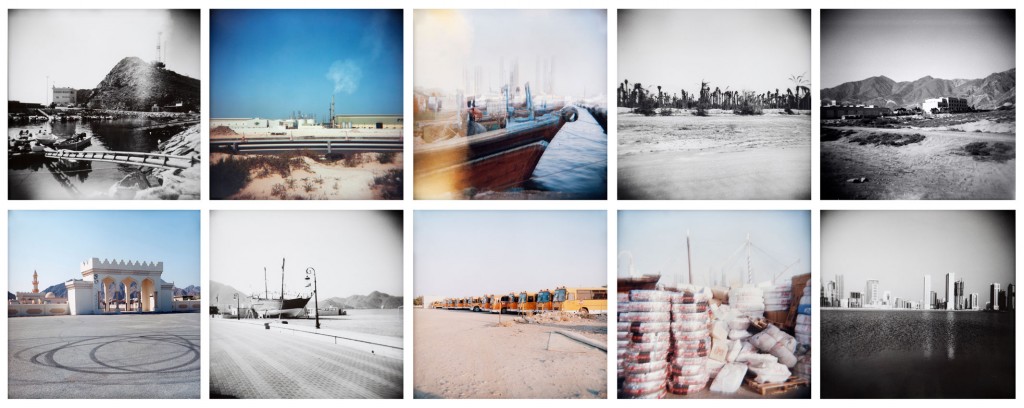

With the upsurge in urban construction, the region’s terrain began to experience radical changes, and much of vernacular architecture was either abandoned or fundamentally transformed. The works of Ziad Antar and Camille Zakharia presented in this exhibition employ the medium of photography to document visible alterations in coastal landscapes of the United Arab Emirates and of Bahrain respectively.

Ziad Antar, a Lebanese-born photographer and filmmaker, worked on his series ‘Portrait of a Territory’ for seven years, capturing landscapes of the UAE between 2004 and 2011. A selection from this series is presented in this exhibition, revealing scenes from Sharjah and Dibba taken in 2009 and 2010. Sharjah, being the only emirate with direct access to two Gulfs, has a long history of maritime activity and international trade through sea routes. Dibba Al-Hisn, an area of Sharjah flanked by the Gulf of Oman on the east, has also practiced sea trade and pearl diving since pre-Islamic times. Through his lengthy exploration, Antar has captured the numerous transformations that the port city has experienced over the past few decades, instilling a feeling of nostalgia in many of his images by manipulating light and depth of field during the photographic process. He has also documented elements that have been introduced into the natural topography as part of modernisation, such as asphalt roads, residential high-rises and industrial factories – additions that have either replaced or considerably impacted existing settlements and raw stretches of land along the coast.

Camille Zakharia, who like Antar was also born in Lebanon, chose another Gulf coast for his exploration. In 2010, he studied vernacular structures along Bahrain’s shoreline. Through his ‘Coastal Promenade’ series, Zakharia documented an array of abandoned fishing huts situated along the coast, which appear to be obsolete amid the country’s current state of economic affairs. Prior to Bahrain’s rapid modernisation, such huts were used as temporary shelters and resting places by local fishermen and pearl divers during their lengthy maritime ventures. As the country’s sources of income changed following the exportation of oil, fishing and pearl diving no longer hold the value they used to in Bahrain’s economy and as such, these architectural structures are no longer a necessity in the country’s coastal territories.